This post is part 2 of a 12 part series about The Truth Project, an in-depth Christian Worldview experience led by Del Tackett and published by Focus on the Family.

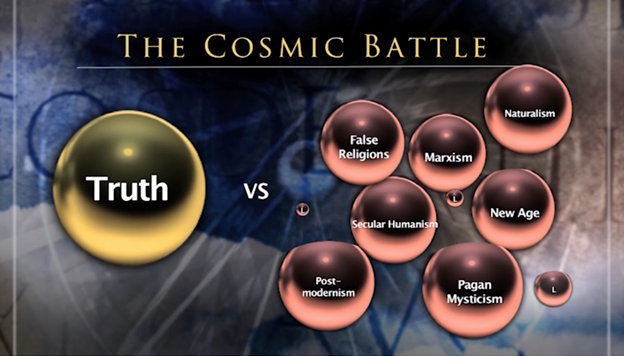

Del Tackett opens up the second talk on philosophy and ethics with a reminder about the cosmic battle. As Christians, we can be taken captive by deceptive philosophies based on human traditions and basic spirits of the world – not according to Christ. We are warned by the Apostle Paul that we can be deceived by false ideas. Paul tells us, “See to it that no one takes you captive by philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the world, and not according to Christ.” (Colossians 2:8)

And that is exactly what has happened in our culture and at many times in the church. People have been taken captive by an alternative, non-Christian view or reality based upon atheistic naturalism. In that worldview, people attempt to explain the origin and meaning of the universe apart from the God who made it.

“See to it that no one takes you captive by philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the world, and not according to Christ.”

Colossians 2:8

Trapped in the “Cosmic Box”

This philosophy is perfectly illustrated by the late Carl Sagan. Sagan opened his famous PBS special, The Cosmos with these haunting words: “The Cosmos is all that is or was or ever will be. Our feeblest contemplations of the Cosmos stir us — there is a tingling in the spine, a catch in the voice, a faint sensation, as if a distant memory, of falling from a height. We know we are approaching the greatest of mysteries.”

Interestingly, Carl Sagan did not open the series with “There is no God.” He could have, but that would have been a too obvious affront to many people’s religious sensibilities at the time. Instead, he snuck in assumptive language. Assumptive language is subtle. It “assumes,” but does not argue for, potentially controversial positions. Here was Sagan’s assumptive language: “The Cosmos is all that is or was or ever will be.” This is the philosophy of naturalism, pure and simple. It’s not observational, testable, or repeatable – in other words it’s not standard operational science. But you may have missed Sagan’s implicit atheism if you weren’t thinking critically about his statement.

Sagan’s worldview or philosophy is philosophical naturalism. He taught the natural world is all there is. God doesn’t exist in his worldview. His philosophy attempts to define everything that exists within the box of the natural or material universe. Tackett calls Sagan’s worldview the “Cosmic Box.”

A similar worldview to Sagan’s atheistic naturalism is pantheism. This adds the element of “god” to the Cosmic Box, but it’s different from Christianity. Instead, pantheism teaches that “god” is part of the natural world and even synonymous with the natural world. In either case of naturalism (atheism) or pantheism, it’s a far cry from the biblical worldview presented in Scripture.

The Christian worldview is very different from Sagan’s naturalism. Biblical Christianity affirms two things that are anathema to naturalism: for one God exists and secondly he has revealed himself to people. In Christianity, all that exists is not inside the cosmic box of naturalism – instead God is separate from the natural world and made the natural world, thus being greater than everything inside Sagan’s Cosmic Box.

What is Philosophy?

With that introduction, Tackett shifts the conversation to philosophy in general. Though philosophy could be defined several ways, he chooses to center on R.C. Sproul’s definition when he says philosophy is “a scientific quest to discover ultimate reality.”

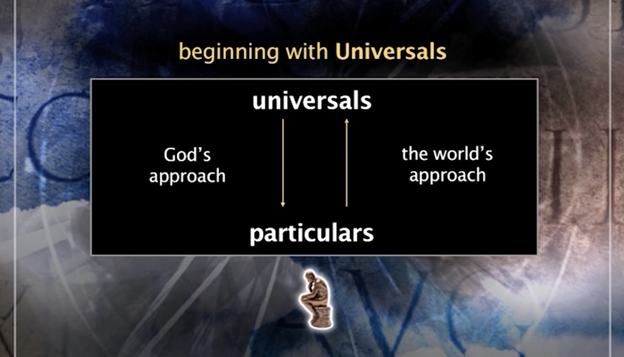

Tackett then explains that philosophy consists of universals and particulars. Universals are the principles that bind everything together. Particulars are the collection of items in the world. For example, 2 + 2 = 4 indicates a universal principle of addition, whereas you can hold 4 “particular” apples in your hands.

Unbelieving philosophers have struggled with a problem for millenia: how can we make sense of the particulars when we don’t know what the universals are? Many philosophers believed if we knew the universals we would have a place for the particulars. The quest on how to arrive at the universal truths has been an aim of philosophy since it began.

The Christian approach to the problem is to understand the universals as God has revealed them to interpret the particulars of God’s creation. For instance, God told us that he created all the living animals (universal) on days 5 and 6 in the creation week so we know that bumble bees, wolves, and yaks (particulars) didn’t evolve from single celled organisms.

On the other hand, non-believing thought has aimed to reason from the particulars to arrive at the universals. Non-Christians try to understand the particulars of the blue whale, the kangaroo, the pygmy owl, and human beings (particulars) and reason from those particulars that all living things must be related through biological evolution (universal). This methodology has generated many contradictory ideas in the history of philosophy.

Non-Christian Philosophies: Dark Inside the “Cosmic Box”

Here is a sampling of the many hollow and deceptive non-Christian philosophies (Colossians 2:8) that thinkers have postulated throughout the centuries. These ideas have arisen from those who reject God’s revelation in Scripture and in Christ.

Materialism: matter is the only reality

Idealism: ideas are the only reality

Empiricism: knowledge comes from experience

Rationalism: knowledge is gained by reason without experience.

Naturalism: true knowledge only comes from scientific study

Determinism: there really is no knowledge, you only react to stimuli

Relativism: there are no absolutes

Mentalism: mind is the true reality and objects exist only as an aspect of the mind’s awareness

Mechanism: everything can be explained in terms of physical or biological causes

Solipsism: self is all you need to know

Subjectivism: knowledge is dependent upon and limited by your own subjective experiences

Intuitionism: knowledge comes from primarily from some kind of inner sense

Hedonism: pleasure is good, pain is evil. If it feels good, it is.

All of these failed attempts to understand reality without God has led to the current philosophical landscape of postmodernism. Britannica.com defines Postmodernism as “a late 20th-century movement characterized by broad skepticism, subjectivism, or relativism; a general suspicion of reason; and an acute sensitivity to the role of ideology in asserting and maintaining political and economic power.” Unbelieving thought has led to postmodernism for the present. Ultimately, unbelievers cannot lay hold of the universals because they have fundamentally rejected the actual universals revealed in Scripture. Because they cannot find viable alternatives to those universals, they become skeptics. They are postmodern.

Anarchy Inside the “Cosmic Box”

Ethics are the transcendent standards for right and wrong. Each philosophical system tends to address ethics and they necessarily flow from the overarching philosophy. Here’s the major problem with cosmic box, naturalistic thinking: there is nothing that someone can do inside the box that is unnatural. If human beings are the product of a random chance, materialistic universe without God, then who determines what is right or wrong? In a universe without God, who makes the rules?

Ethics tends to deteriorate into moral coercion without a transcendent tether. In other words, might makes right. Whether that “might” comes from the strength of an individual, the power of weapons, or a 51% voting block, ethical standards flow from coercive action. There may be a modicum of justification for unbelieving ethics through utilitarianism or pragmatism which aims to impose standards for the majority. However, the minority is always oppressed where these non-Christian ethical systems are practiced.

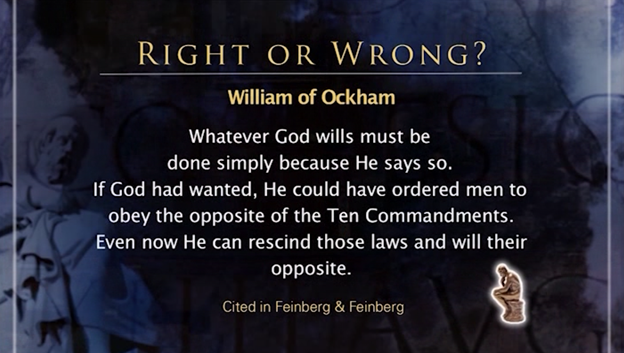

One method to ground ethics was in the Divine Command Theory. Tackett then introduced William of Ockham (1287-1347). Ockham proposed an ethical system that attempted to ground ethical prescriptives in an arbitrary God. Ockham wrote, “whatever God wills must be done simply because he says so. If God had wanted, he could have ordered men to obey the opposite of the Ten Commandments. Even now He can rescind those laws and will their opposite.” This Divine Command Theory suggests that God’s will is the foundation of what is right and wrong. The problem with this theory is it’s not biblical. In several places in Scripture, we find the ethical imperative tied to God’s character – not his will. Consider “Be holy because I am holy.” (1 Peter 1:16)

Ethical Implications in Naturalism

Going back to non-Christian ethical systems, evolutionist William Provine forwarded several philosophical and ethical implications in his naturalistic worldview.

- No gods or purposeful forces.

- No ultimate foundation for ethics.

- No free will.

- No life after death.

- No ultimate meaning in life.

- No free will.

More importantly for our purposes, Dr. Provine in his debate with Phillip E. Johnson (April 30, 1994) admits “there’s no reason whatsoever that ethics can’t be robust with no ultimate foundations for ethics.” Provine is being direct and honest. Because God is not in charge of the universe because he does not exist, ethics has no foundation. It may be sad and it may feel empty, but it is consistent in Provine’s worldview.

“There’s no reason whatsoever that ethics can’t be robust with no ultimate foundations for ethics.”

Dr. William Provine (Evolutionist & Naturalist)

Provine’s straightforward ethical implications of his naturalism has played out in our society. Because most people do not look to transcendent, God-based ethics, they instead look at horizontal practices to determine what is right and wrong. Essentially, what is being practiced in society is now the basis for what is good and bad – not God’s standards.

R.C. Sproul points out how this has played out in a subtle vocabulary shift in recent decades. Sproul writes, “Ethics, or ethos, is normative and imperative. It deals with what someone ought to do. Morality describes what someone is actually doing. That’s a significant difference, particularly as we understand it in light of our Christian faith, and also in light of the fact that the two concepts are confused, merged, and blended in our contemporary understanding.”

Sproul argues that our world confuses the two, very different concepts of ethics and morality. Whereas ethics aims for what “ought” to be done, morals describe what “is”. This is the reason our society is obsessed with surveys. For instance, if people believe that 10% of the population are practicing homosexuals, then at least a person can justify homosexual behavior knowing that he’s part of the 10% homosexuals in the population. That justification completely ignores what God has spoken about homosexuality or any ethical behavior. But it makes sense when one justifies morality based on the statistical practices in society.

Worldview: Structure for Philosophy & Ethics

Tacket then shifts the lesson to worldview. He divides formal and personal worldviews in an effort to make this session more personal to students. To begin, he says, “A formal worldview is a comprehensive set of truth claims that purports to paint a picture of reality.” Examples of formal worldviews are Islam, Secular Humanism, Naturalism, New Age, and Christianity. This is how belief sets are structured in our world, but it’s not always practiced like that. Especially in the church.

Concerning the lack of coherent understanding of worldview in the church, Charles Colson writes, “The church’s singular failure in recent decades has been the failure to see Christianity as a life system, or worldview, that governs every area of existence.” In other words, the church has failed because it has not seen Christianity as a comprehensive system of thought that can govern every area of our understanding. Most people don’t view Christianity as a coherent worldview.

On the practical side, there’s also a “personal worldview.” A personal worldview is the “set of individual truth claims that you have embraced so deeply that you believe they reflect what is really real, and therefore they drive what you think, how you act, and what you feel.” Few people hold to a formal worldview with all of its philosophical, ethical, and practical applications. But we all have a personal worldview. Personal worldviews are collections of true things and lies. And the only way to better align with truth, that which is revealed in Scripture, is through renewing our mind.

“The church’s singular failure in recent decades has been the failure to see Christianity as a life system, or worldview, that governs every area of existence.”

Charles Colson from How Now Shall We Live?

Application: Transformation Through Mind-Renewal

Tackett concludes this session with the key to changing our philosophy, ethics, and worldview. We don’t just happen to get a proper mindshift. Instead, it occurs through renewal of our mind in Christ. Paul tells us, “Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.” (Romans 12:2) The Greek term for transformed in this passage is metamorphoo (μεταμορφοῦσθε). It is the same term from which we get “metamorphosis” – as in a caterpillar turning into a butterfly. This is a similar kind of transformation that God wishes to enact in us. He desires to transform us more and more into Christ.

We must be transformed for us and for our children. We must partake in a real metamorphosis for the glory of God. If we do not believe the truth claims of God and act in accordance with them, where will the light come from?

Featured Image Source: aleteia.org