Relativism defined, its offshoot moral relativism, and how it’s unlivable in the world God created from whom our morality flows.

In 2016, Oxford Dictionary’s Word of the Year was “post-truth”. Post-truth is an adjective defined as ‘relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief’. The idea behind post-truth is that our culture is less interested in what is objectively true – outside of ourselves – and more interested in personal or community experience. In one sense, we live in such a way that feelings override facts. Oxford Dictionary wasn’t alone.

- Time Magazine acknowledged a new kind of world when they followed up their “Is God Dead?” cover from 1966 with a 21st century version, “Is Truth Dead?” in 2017.

- Donald Trump’s Presidency was unique by labeling the “fake news” industry – a bold allegation that mainstream news reporting makes up the news and doesn’t report the truth.

- Social media experience can be a type of post-truth when we follow those who agree with us and unfollow (or unfriend) those who don’t. That produces the proverbial ‘echo chamber” where we only see posts from people who “echo” our own positions.

What does this say about our culture? When we elevate our own opinions above reality, we have entered a new era. In this era, there is no unifying system of thought that binds culture together. Instead, it’s more of a collection of competing narratives and worldviews. This is the post-truth world.

In this post, we want to address one of the main reasons we live in a world where the concept of truth has collapsed which is relativism. We want to define relativism, understand more about its offshoot moral relativism, and show how it’s unlivable in the world God created from whom our morality flows.

“I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery. You shall have no other gods before me.

Exodus 20:2-3

What Is Relativism

To start, let’s understand what relativism is. Matt Slick on carm.org wrote, “Relativism is the philosophical position that all points of view are equally valid and that all truth is relative to the individual. This means that all moral positions, all religious systems, all art forms, all political movements, etc., are truths that are relative to the individual.”

Relativism (or subjectivism) may seem fine when you’re talking about your favorite movie, music, or cookies. Not everyone shares the same opinion on the best film, cookie, or song. Those kinds of things fall into more subjective categories. However from a biblical perspective, relativism is not accurate when you’re talking about overarching truth, morals, or religion.

The opposite of relativism is objective truth. According to J. Warner Wallace.

“We begin by describing the difference between ‘objective’ truth (which is rooted in the nature of the object under consideration and transcends the opinions of any subject considering this object), and ‘subjective’ truth (which is rooted in the opinions and beliefs of the subjects who hold them and vary from person to person).”

So in relativism, truth is centered in the individual or community. Truth is derived from the subject – or so says the relativist. On the other hand, the traditional position holds that truth is objective. Truth is not rooted in the person observing a thing – truth transcends the person. For instance, a person may think he can fly but the moment he steps out of an aloft airplane the law of gravity will speak louder than his opinion. Without a parachute, gravity will win and relativism will lose.

Moral Relativism In Action

Moral relativism is relativism in ethics. Greg Koukl says “Moral relativism teaches that when it comes to morals, that which is ethically right or wrong, people can and should do whatever feels right for them.”

There are many ways moral relativism manifests itself in our culture. Here are a few statements that illustrate how moral relativists speak:

- “That may be true for you, but it’s not true for me.”

- “It feels right to me.”

- “…for there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so. ” Hamlet (Shakespere)

- “Live your truth.” – Steve Maraboli

- “Find your truth within you.”

- “Face your fears; Live your passions, be dedicated to your truth.” Billie Jean King

- “Different strokes, for different folks.”

A good way to understand how moral relativists think is through a story. In his book, Relativism: Feet Firmly Planted in Mid-Air, Greg Koukl recounts a conversation with an assistant in a doctor’s office when he wanted to get her take on morality.

“‘Can I ask you a personal question?’ I asked. She paused in her work, uncertain how to respond. ‘I’m reading a book on ethics and I want to know your opinion about something.’

‘Oh,’ she said. ‘Okay’.

‘Do you believe that morality is absolute, or do all people decide for themselves?’

‘What do you mean by morality?’ she asked.

‘Simply put, what’s right and what’s wrong,’ I answered…‘Is murder wrong?’ I asked. ‘Is it wrong to take an innocent human life?’

She waffled. ‘Well…’

‘Well . . . what?’

‘Well, I’m thinking.’

I was surprised at her hesitation. ‘What I’m trying to find out is whether morals, right and wrong, are something we make up for ourselves or something we discover. In other words, do morals apply whether we believe in them or not?’

I waited. ‘Can we say that taking innocent life is morally acceptable?’

‘I guess it depends,’ she said tentatively.

‘Depends on what?’ I asked.

‘It depends on what other people think or decide.’

I’ll make this really easy, I thought. ‘Do you think torturing babies for fun is wrong?’

‘Well…I wouldn’t want them to do that to my baby.’

‘You’ve missed the point of my question,’ I said, a bit exasperated. ‘I may not like burned food, but that doesn’t mean giving to me is immoral. Do you believe there is any circumstance, in any culture, in which torturing babies just for pure pleasure could be justified? Is it objectively wrong, or is it just a matter of opinion?’

There was a long pause. Finally, she answered, ‘People should be allowed to decide for themselves.’

In reflecting on this conversation, I realized that I would never want this woman on a jury. I would never want her as a social worker, as an employee of a bank, as a teacher, as any kind of medical practitioner, or in any branch of law enforcement. I would not want a person who thinks like this in any position of public trust.

Sadly, this woman’s view of ethics is repeated time after time in every level of society. In reality, if she was awakened in the middle of the night by the plaintive screams of a young child being tormented by her neighbor next door, I’m sure she would be horrified by the barbarism. Her moral intuitions would immediately rise to the surface and she’d recoil at such evil. In a discussion of the issue, however she seemed incapable of admitting that even this egregious wrong was actually immoral.”

Three Fatal Flaws of Moral Relativism

In addition to the underlying revulsion most people have to extreme moral relativism (ex. It’s not wrong to torture babies for fun), there are other flaws that render moral relativism unlivable. With a hat tip to Greg Koukl, here are three of moral relativism’s fatal flaws:

Fatal Flaw #1: Moral Relativists Cannot Accuse Others of Wrongdoing

Relativists deny objective wrongdoing. And since morality does not extend beyond a person or group, relativists cannot consistently accuse others of wrongdoing and remain consistent. No matter how blatantly evil something is like murder, rape, racism, child abuse, or genocide, relativists can only say they don’t like it. They cannot criticise it on objective grounds. Or as Koukl says, “When right and wrong are a matter of personal choice, we surrender the privilege of making moral judgments about the actions of others. However if we are certain that some things must be wrong and that some judgments against another’s conduct are justified – then relativism is false.”

Fatal Flaw #2: Moral Relativists Can’t Complain About the Problem of Evil

Most atheists point to the problem of evil as a reason God cannot exist. After all, if he did exist he could do away with evil – or so says the atheist. However, the moral relativist has a more serious problem. The relativist can’t even say there is such a thing as objective moral evil. In their worldview, nothing is evil. There is no moral standard outside of themselves to which they can appeal. This doesn’t mean they don’t actually believe in evil, but their moral relativism prevents them from consistently affirming objective evil.

Fatal Flaw #3: Moral Relativists Can’t Make Charges of Unfairness or Injustice

Fairness aims for equal treatment according to an external standard. Justice entails punishing those who are guilty of a crime. Our laws aim for people to be judged fairly. But in moral relativism, there is no external standard of right or wrong. It doesn’t exist. Relativism rejects the standards of fairness and justice since right and wrong are relative to each person or community. That’s why they lose the right to cry, “that’s not fair!” After all, they rejected fairness when they affirmed moral relativism.

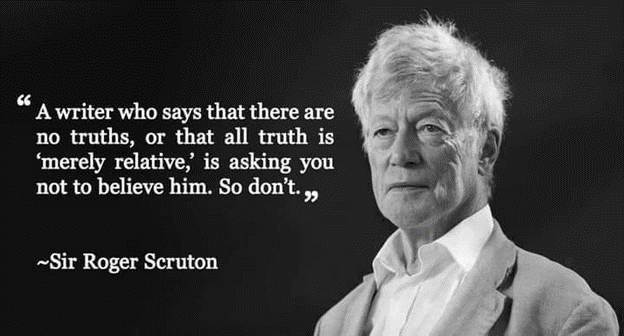

Bottom line, moral relativism is essentially unlivable. Nobody can have discussion about anything disputable without appealing to standards outside of themselves. That’s why whenever we run across a moral relativist we may do well to grab our wallet and slowly back away from the person. Another approach is to ignore them. Philosopher Roger Scruton once quipped about moral relativists: “A writer who says that there are no truths, or that all truth is ‘merely relative,’ is asking you not to believe him. So don’t.”

Self-Defeating Relativistic Statements

(with replies)

That’s true for you, but not for me.

(Does that work the same with gravity?)“There’s no objective truth.”

(Is that statement true?)“Doubt everything!”

(Should I doubt that?)“All truth is relative.”

(Is that statement also relative?)“Nobody has the truth.”

(Are you saying that’s true?)“Everything is meaningless.”

(What do you mean by that?)

Basis of Biblical Morality: God’s Character

Moral relativism stands in direct conflict to biblical morality. In the Bible, we find a very different picture of subject-based or community-based morality. Instead, we find an outside standard for right and wrong in God. He directs how humans are to live in harmony with himself and others. Those directives are found in numerous places, but a good summary of them are found in the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:2-17, Deuteronomy 5:6-21).

The basis for what is moral and immoral for human beings is in God’s character. There are a few passages that directly connect our ethical behavior to the character of God.

- We ought to love because God loved us (1 John 4:19).

- We ought to be holy because God is holy (1 Peter 1:15).

- We ought to be merciful because God is merciful (Luke 6:36).

There are more ethical concerns besides love, holiness, and mercy for the Christian. But for the purposes of this discussion we must understand the grounding of any ethical system. In biblical morality, that grounding is in God’s character. So whatever is right and wrong is based on what God reveals to us in Scripture. And the ethics he reveals are grounded in his character. This is a far cry from moral relativism that looks no further than the individual or community for ethical directives.

Moral Relativism’s Consequences

Moral relativism is essentially moral anarchy. When morality is based upon everyone’s individual or collective opinions, then there is no external standard to guide moral decisions. It’s not surprising to see moral relativism in our nation where we have removed God out of the public sphere. The Bible describes a time when ancient Israel dealt with something similar. “In those days there was no king in Israel. Everyone did what was right in his own eyes.” (Judges 21:25) That was moral relativism.

There are other examples of moral relativism that you may recognize.

- Killing a baby is prosecuted as murder while killing a pre-born baby is celebrated as a “right” is an example of moral relativism.

- Unequal treatment of individuals under the law. High-level politicians who take bribes from companies are not prosecuted, while low-level bureaucrats are prosecuted for similar crimes is an example of moral relativism.

- Media treatment of left-wing groups is generally sympathetic while treatment of right-wing groups is generally negative. That is moral relativism.

- Islamic countries uphold jihadis as heroes when they murder non-combatants, while at the same time prosecuting murderers. That is moral relativism.

Application: Moral Relativism is Unlivable

Moral relativism is not true. Because there is a standard from which all morality flows, namely God, then morals necessarily are not grounded in ourselves. Anyone who argues for moral relativism will inevitably expose his hypocrisy when he himself is wronged. If you steal their car (and they forgot to pay their insurance), they will claim that action wasn’t fair, it was unjust, or it was wrong. Whenever moral language arises in their protestations, they are appealing to a transcendent law. This is a tacit acknowledgement that God makes the rules – not us. Ultimately, moral relativism is an unlivable philosophy because it does not align with the world God created.

Resources

What is Truth? – Steven Lawson

A Critique of Moral Relativism (video: 14:19) – InspiringPhilosophy

Seven Fatal Flaws of Moral Relativism – Greg Koukl

10 Things You Should Know About Christian Ethics – Wayne Grudem

Image credit: paul_wong on Unsplash